Global Dispatcher Interface

Richard Peters

Peters Research Ltd

School of Science and Technology, The University of Northampton, UK

This paper was presented at the 6th Symposium of Lift and Escalator Technologies (CIBSE Lifts Group and The University of Northampton) (2016). This web version © Peters Research Ltd 2016

Keywords: dispatcher, group traffic control, interface, conventional control, destination control

Abstract

The efficiency of a lift group depends heavily on its dispatcher (also known as the group traffic control). A dispatcher decides how a group of lifts serve the passenger demand, normally based on calls placed on the system by the passengers. Defining a common, global dispatcher interface makes it easier for simulation and real word systems to talk to each other. The author draws on practical experience to consider if the next generation of dispatchers should be centralized or decentralised, and to suggest a dividing line between lift controller and lift dispatcher functions. Having addressed dispatcher architecture and scope, the requirements of a global dispatcher interface are considered. These include, but are not limited to single deck cars, double deck cars, and multiple independent cars in a shaft. The dispatcher interface also needs to consider different user interface options including landing call buttons, car call buttons, destination based input, together with associated indicators and displays.

1 Introduction

The early group traffic control systems were human dispatchers who stood in the main lobby during the morning uppeak directing passengers and in-car attendants who controlled individual cars. Humans gave way to systems utilising relay logic, which in turn gave way to hybrid relay/electronic controllers, programmable logic controllers and microprocessor based systems. Many modern dispatchers apply artificial intelligence, mimicking the intelligence and insight of the original human dispatchers [1].

The responsibilities of the dispatcher and controllers in most current systems mimic the division of labour between the early human dispatchers and in-car attendants. The dispatcher allocates the landing or destination calls to individual cars. The controller (in-car attendant) dictates how the allocation landing calls and car calls are served, also managing door functions.

A dispatcher needs to communicate with passengers, typically through buttons and indicators, and with the lifts to allocate calls. A proprietary dispatcher interface has been available since 1998 [2]. It has been widely applied in simulation, and with modifications in actual installations. However, the interface was built for simulation without consideration of real time systems and has evolved to support new technology rather than been designed for it.

This paper suggests moving the dividing line between dispatcher and controller functions. It proposes a second generation global dispatcher interface as a basis for developing dispatchers which are easily interchangeable and that apply exactly the same code in simulation and real world systems.

2 System Architecture

2.1 Centralised and distributed control

There is a vast amount of data to exchange within a modern lift installation and a number of possible methods by which the data can be collected and processed [3].

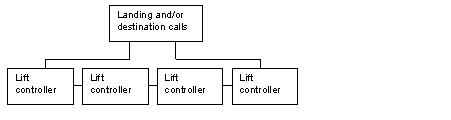

A common approach is distributed control, see Figure 1. Each lift controller receives all information about new landing (or destination) calls over a network. Each lift controller performs its own calculations, providing a bid for the call according to the traffic control algorithm. The master lift control compares the bids and awards the call.

Figure 1 Distributed control (from Figure 9.6 CIBSE Guide D: 2015 [3])

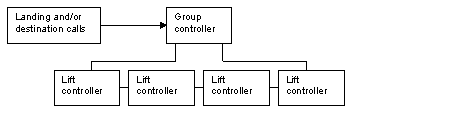

Alternatively, a dedicated group controller, sometimes an industrial computer, collects the data and allocates landing calls to a lift according to the traffic control algorithm, see Figure 2. As with distributed control, once a lift has been allocated a call, it is normally the lift controller that manages how calls are served.

Figure 2 Centralised control (from Figure 9.5 CIBSE Guide D: 2015 [3])

With distributed control, if the master lift fails, one of the other lifts automatically takes over the group control functions. With centralised control, a backup group controller is often included in case of failure. Both approaches can work. In new installations, distributed control tends to be favoured. In modernisation, centralised control allows for the dispatcher to be upgraded while keeping the existing controllers. Centralised control can also allow for a range of new controllers from different sources to use the same dispatcher.

2.2 Controller design issues impacting the dispatcher

For the dispatcher designer, centralised control is simpler and more flexible. However, there are other controller design issues which impact dispatcher optimisation.

Once a lift has been allocated a call, it is normally the lift controller that manages how its calls are served. To provide good performance, it necessary for the dispatcher to make assumptions as to how the lift controller is going behave once a call is allocated. Although collective control is a prerequisite for almost all modern lift groups, when the fine details are considered, its implementation varies.

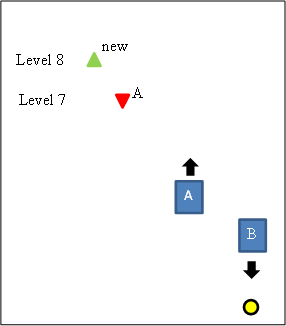

For example, consider the scenario given in Figure 3. Lift A is travelling to pick up a down landing call at level 7. Once lift A arrives at level 7 it will reverse direction. As it travels towards level 7, before it reaches its slow down point, a new up call is registered at level 8. The dispatcher determines the best solution is for lift A to change its target floor from 7 to 8 so that it can serve the up call at level 8 (and its subsequent car call) before reversing and serving the down landing call at level 7.

At what point is it too late to change lift A’s target floor from level 7 to level 8? Some lift controllers will commit to the reversal at level 7 as soon as it becomes the target floor. Other controllers may allow the change, but the point at which the target is fixed is not consistent.

In the context of conventional control, a mistake can be corrected; if the landing call at level 8 is allocated to lift A, but the lift reverses at level 7, the level 8 call can be re-allocated to lift B. However, with a destination control system, the passenger has been told to wait for lift A, and must wait for a complete round trip of the lift before his or her call is answered. Other scenarios yield similar issues. Without a time-consuming dispatcher design and test process involving analysis of dispatcher logs post installation, some dispatcher errors only manifest themselves in long waiting times. Sometimes these errors go uncorrected for the lifetime of the installation.

Figure 3 Scenario leading to potential dispatching error

In other scenarios, the dispatcher designer may want the collective control rules followed by most lift controllers to be broken, for example where a reverse journey (initially taking a passenger in the opposite direction to their destination) is the best compromise option in a destination control system [4].

2.3 Intelligent door control

Intelligent door control provides one of the best opportunities to improve current dispatcher design. For example, destination control systems do not take advantage of the information they have about the number of passengers expected to alight and load a lift when considering when to start closing the doors. This can be observed if travelling to a floor when it is known that only one passenger is alighting. In this instance the dispatcher could tell the lift doors to start closing immediately that the door beams are re-established. In all systems observed, the normal lift controller dwell times are left to expire before the doors close, often wasting between two and four seconds.

2.4 New requirements

In the case of two or more independent cars in a single shaft, dispatching become increasingly complex with the choices made for the operation of each car being impacted by the status and position of all the other cars. For example, with three cars (A, B and C) in the same shaft, if a dispatching solution involves car A being held because car B is being held to avoid collision with car C, the ability of car A to make optimum dispatching decisions becomes increasing difficult. Car A needs a lot of information to make an optimum dispatching bid for a call; a centralised solution with a car A simply accepting travel commands will require significantly less network traffic.

2.5 Second generation global dispatcher interface

The global dispatcher interface proposed in the following sections assumes centralised control. Furthermore, operation logic commonly managed by the lift controller is assigned to the dispatcher. The lift does not manage calls, it goes where it is told to, and accepts door open and close commands directly from the dispatcher. Yielding the minimum decision making to the lift controller and other devices minimises the opportunity for the systems to conflict and for inconsistency in dispatcher performance with different controllers. This allows the dispatcher designer the best opportunity to optimise performance and maximise portability between lift controllers. It also simplifies the task of implementing a lift controller and the components needed to create user interfaces.

3 The Interface

The interface allows for both conventional and destination calls within the same lift group. It can accept destination and conventional calls or operate as a hybrid accepting both conventional and destination calls.

For brevity, this paper describes the interface for single deck lifts only. Future publications will account in more detail for double deck lifts, multiple cars operating in the same shaft, and for movement in three dimensions.

The paper describes the open loop version of the dispatcher; closed loop options will be described in future publications. Close loop operation allows the dispatcher to confirm messages have been received successfully and to test if theoretical possibilities are practically achievable, e.g. can a lift stop in time for a new call placed while the lift is travelling.

The interface could be implemented with different mechanisms. Proof of concept tests have been completed using messages communicated over TCP/IP applying Protocol buffers. This is a language-neutral, platform-neutral, extensible mechanism for serializing structured data [5]. For memory and speed, all variables are integers, hence the use of grams rather than kilograms and millimetres rather than meters.

To reduce network traffic, data is divided into static and dynamic data. Static data does not change and only needs to be communicated during initialisation.

4 Static Data

A summary of the data required is given in Table 1. MAX_LIFTS and MAX_FLOORS define the limit of number of floors and number of lifts that the dispatcher will manage. MAX_RISERS corresponds to the number of destination input device risers; destination input devices with the same riser number are in the same [x, y] position on different floors.

Table 1 Static data

| Variable | Description |

| Velocity[MAX_LIFTS] | Rated lift velocity (mm/s) |

| Acceleration[MAX_LIFTS] | Rated lift acceleration (mm/s/s) |

| Jerk[MAX_LIFTS] | Rated lift jerk (mm/s/s/s) |

| DoorPreOpen[MAX_LIFTS] | Door pre-opening (ms) |

| DoorOpen[MAX_LIFTS] | Door open time (ms) |

| DoorClose[MAX-LIFTS] | Door closing time (ms) |

| MotorStartDelay[MAX_LIFTS] | Motor Start Delay (ms) |

| LevellingDelay[MAX_LIFTS] | Levelling delay (ms) |

| Home[MAX_LIFTS] | Default parking floor (normally ground). Refers to lower deck if lift has more than one deck. |

| Capacity[MAX_LIFTS] | Nominal lift capacity (g) |

| FloorArea[MAX_LIFTS] | Floor area of car (mm2) |

| NoFloors | Number of floors served |

| NoLifts | Number of lifts |

| FloorPositions[MAX_FLOORS] | Positions of floors (mm above reference) |

| FrontDoors[MAX_FLOORS] | To indicate if front doors on this landing |

| RearDoors[MAX_FLOORS] | To indicate if rear doors on this landing |

| NoDestinatinInputRisers | Number of destination input riser positions |

| WalkingDistance[MAX_LIFTS][MAX_RISERS] | Walking distance from destination input risers to lifts (mm) |

| WalkingSpeed | Passenger walking speed (mm/s) |

| PassengerLoadingTime | Passenger loading time (ms/passenger) |

| PassengerUnloadingTime | Passenger unloading time (ms/passenger) |

| MinPhotocellDelay | Minimum photocell delay (ms) |

| MinDwellCarCall | Minimum dwell time for car call (ms) |

| MinDwellLandingCall | Minimum dwell time for landing call (ms) |

| DestinatinIndicators[MAX_FLOORS] | 1 or 0 to indicate if messages are required for destination indicators on each floor |

| DirectionIndicators[MAX_FLOORS] | 1 or 0 to indicate if messages are required for directional indicators are on each floor |

| CarIndicators[MAX_LIFTS] | 1 or 0 to indicate if messages are required for destination indicators on each floor |

5 Dynamic Data

5.1 Adding a call to the dispatcher

Calls can be added to the dispatcher with messages according to Table 2.

Table 2 Call message

| Variable | Description |

| Index | Unique index created by system placing call |

| CallType | Car call, up landing call, down landing call, destination call |

| Origin | Floor index of origin of call (required for landing calls and destination calls) |

| Destination | Floor index of destination of call (required for destination calls and car calls) |

| OriginSide | Front or rear |

| DestinationSide | Front or rear |

| Riser | Destination input riser position (required for destination calls |

| ExclusiveGroup | Exclusive group index where groups of passengers are to be separated (optional and only available for destination calls) |

| PersonID | Person ID (optional and only available for destination calls). This will be obtained from a card reader or similar on the destination input device |

| Special functions | to be added |

The dispatcher should respond with a message in the following format, see Table 3.

Table 3 Call message response

| Variable | Description |

| Index | Index provided in call message |

| Allocation | Allocated car (zero for no allocation) |

| Error code | Error code to indicate why no allocation made |

5.2 Security

For systems requiring the dispatcher to manage security, the dispatcher needs to know if a person is allowed to travel to the floor requested. In this instance the dispatcher will send a message to the security system to request authorisation, see Table 4.

Table 4 Security message

| Variable | Description |

| PersonID | ID of person requesting call |

| Destination | Requested destination |

The response from the dispatcher is described by Table 5.

Table 5 Security call message

| Variable | Description |

| PersonID | ID of person requesting call |

| Authorisation | 1 or 0 for true or false |

Note that there are there are other ways to manage security. For example, on presentation of the security card (or other ID device), the destination input device may only present the floor available to that person. In this instance, the dispatcher does not need to be involved in the management of security.

5.3 Lift status

Lift status messages are sent to the dispatcher on initialisation and subsequently when any variable changes. Messages may contain one or more variable updates.

Table 6 Lift status messages

| Variable | Description |

| LiftNo | Lift car this message corresponds to |

| CarService | Indicating if lift is in automatic, manual or out of service |

| CurrentLoad | Current car load (g). During loading and unloading of the car, there should be damping of this variable. When the lift is moving, no status updates for this variable are required. |

| CurrentFloorNo | Current floor number, updated when the lift reaches its destination. Intermediate floor numbers are not required and will be interpolated from lift dynamics. |

| DoorBeams | Flag indicating if door beams are interrupted |

| DoorBeamsRear | Flag indicating if rear door beams are interrupted |

| TravelStatus | Flag to indicate if lift is travelling |

| DoorStatus | Current status of the front doors (1 fully open, 2 closing, 3 fully closed, 4 opening, 5 nudging) |

| DoorStatusRear | Current status of the rear doors (1 fully open, 2 closing, 3 fully closed, 4 opening, 5 nudging) |

Table 7 Lift command messages

| Variable | Description |

| LiftNo | Lift car this message corresponds to |

| CloseDoors | Close lift doors |

| NudgeDoors | Close the lift doors applying nudging operation |

| SetDestinationFloor | Start journey to floor when doors have closed. |

| OpenDoors | Open doors on arrival, or immediately if lift is not travelling. If doors are closing, reverse. |

5.4 Lift dynamic configuration

The purpose of the messages in Table 8 are to allow lifts to be locked off from selected floors. This is sometimes required if a floor is unoccupied.

Table 8 Configuration message

| Variable | Description |

| LiftNo | Lift car this message corresponds to |

| FloorNo | Index of floor this message corresponds to |

| FrontLocks | 1 or 0 to allow front lift doors to open on this floor |

| RearLocks | 1 or 0 to allow rear lift doors to open on this floor |

5.5 Indicator status messages

The following messages in Table 9 are to address indicators on the landings and in the cars.

Table 9 Status messages

| Variable | Description |

| LiftNo | Lift car this message corresponds to |

| FloorNo | Floor this indicator is on |

| Direction | 1 or 0 corresponding to up or down |

| DestinationFloor | Destination floor to add or remove |

| Status | 1 or 0 corresponding to on or off |

6 Conclusions

To design reliable and portable dispatchers, a well-defined dispatcher interface is required. This should work with both simulation and in real systems.

This paper gives a high level description of a global dispatcher interface proposed for the next generation of dispatchers. The author invites constructive comments and suggestions to help improve and develop what it is anticipated will become a de facto standard. A more detailed specification and examples will be available to those who wish to contribute.

REFERENCES

- G. Barney and L. Al Sharif, Elevator Traffic Handbook: Theory and Practice, Routledge, 2015.

- Peters Research Ltd, “Elevate,” [Online]. Available: https://www.peters-research.com/index.php/elevate. [Accessed 1 July 2016].

- R. Peters, “Lift traffic control,” in CIBSE Guide D:2015 Transportation systems in Buildings, The Chartered Institution of Building Services Engineers, 2015.

- S. Gerstenmeyer and R. Peters, “Reverse Journeys and Destination Control,” in 4th Symposium on Lift & Escalator Technologies, Northampton, 2014.

- Google, “Protocol Buffers,” [Online]. Available: https://developers.google.com/protocol-buffers/. [Accessed 1 July 2016].

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author is grateful to Dr Albert So who first persuaded him to implement a dispatcher interface in Elevate, Dr Mike Pentney for designing the original Elevate Windows DLL interface, Dr Jonathan Beebe for his informative work with open standard information models, and for Mr Jim Nickerson for his expertise in developing the Elevate interface in a real time environment with modern software technology.